“The task of leadership is not to put greatness into people, but to elicit it, for the greatness is already there”

John Buchan

2001

It was another Friday on board HMS OCEAN, alongside in Plymouth and I was running the weekly Squadron Orderly Room. This was the formal opportunity to deal with defaulters and to address issues with the careers of the men in 9 Assault Squadron Royal Marines (9ASRM). Over the last 18 years I have often reflected on an event that occurred at that Orderly Room and how it affected the lives the defaulter in front of me, Marine Anthony Brisley and me! Whilst I was not aware of John Buchan’s words at the time; they more than fit the outcome, as I will now reveal.

Marine Brisley was a driver assigned to HMS Ocean’s Vehicle Deck Party. Ocean was an amphibious helicopter and landing craft ship. The three man team Party had the duties of controlling the loading and unloading of the ship’s vehicle deck and also the preparation of underslung loads for the helicopters. The rest of the Squadron crewed the four Landing Craft Vehicle and Personnel (LCVP).

Marine Brisley was a bit of a character from West London; mischievous, cocky, always one for the backchat or rejoinder. He seemed to be at the centre of any trouble and was always getting caught. He was in front of me, as a defaulter, for yet another misdemeanour that was bringing the good name of the Squadron into disrepute amongst the rest of the Ships Company and causing me and my Sergeant-Major (‘George’ Patrick) the inevitable headaches and administrative work we could well do without. My chat with the Sergeant Major before the Orderly Room saw us discussing our deep unhappiness at Brisley’s performance and what our options were for getting rid of him. We were due to deploy to the Mediterranean with a raft of exercises and port calls on the horizon. I did not need bad blood in the Squadron!

The leadership moment

In marched Brisley. I was ready to give him a resounding dressing down, however, something in his eye told me not to. His whole demeanour spoke to me of regret; for what he had done, for causing the Squadron and me embarrassment and for being a poorly behaved Marine.

“What is wrong with you Marine Brisley?” I asked.

“Well Sir, I am sorry for what I have done but I am really unhappy,” he responded.

“What is the cause of your unhappiness Marine Brisley?” I asked.

“I am bored Sir, I am fed up being a driver and want to do more with my life.”

“What can I do to help you?”

“You’ll laugh if I tell you Sir.”

“I will try not to.”

“Let me change specialisation, I want to be a Drill Instructor!”

My response

I laughed. The thing is, that in the Royal Marines, the Drill Instructors are all Non-Commissioned Officers, the epitome of smartness, discipline and Corps Values, everything indeed that Marine Brisley was not!

I explained to him that even if I thought this a reasonable course of action for him, he would have to earn a recommendation for promotion, attend and pass a Junior Command Course and be promoted to Corporal (Cpl), then after serving as a Section Commander in a Commando Unit he would then have to apply for and be selected for Drill Instructor training. As a Cpl Drill Instructor he would then be assigned to Recruit Training where he would take 60 or so fresh recruits on the day they join the Royal Marines at the Commando Training Centre and train, coach and mentor them through their 32 weeks of arduous training to win their Green Berets. He would be providing them with a model of discipline, leadership and Corps values. Was that really what he wanted to do and was he capable of being that man?

The outcome

“Yes Sir, that is exactly what I want to do and be. I want to train recruits and lead marines. That is what I joined the Royal Marines to do. I was not given an option. I never wanted to be a driver!”

“Okay Marine Brisley. Here is what is going to happen. I am going to give you a chance to prove to yourself and to me that you have got what it takes. In six weeks time we will be conducting a ship visit to Valletta in Malta. The Captain will host an Official reception for the local dignitaries and it will be the first opportunity for the UK to showcase this new ship to our allies, partners and friends in the region. The Captain asked me if we, 9 ASRM, could lay something special on for the Sunset Ceremony. I have in mind that we put on a bit of a drill display and I want you to lead it. You choose the men, work up the routine, train and drill them then put on the display. Can you and will you do that?”

“Yes Sir, I will give it a crack!”

“No Marine Brisley, a crack is not good enough, this needs to be first rate. You will need to pull out the stops.”

“Leave it to me Sir, thank you for putting your faith in me.”

What have I done?

At that point I dismissed Marine Brisley and a bemused Sergeant Major asked me what I had just done? I had given him a chance; that was all. Something told me that this was what he needed.

The following Monday at our morning Parade, I informed the Squadron that Marine Brisley would be devising the drill display for Malta and would be selecting and training the squad to conduct it. There was a collective groan from the men. I was not confident in the outcome.

Brisley’s leadership

A few days later the Sergeant Major told me that it was not going well. The men were refusing to work for Brisley and he was pulling his hair out! I recall sitting him down and asking him how it felt and what the cause was of the men refusing to support him. He was angry and full of blame for them on their professionalism and lack of discipline. I remarked that it sounded like the pot calling the kettle black; he had that epiphany moment and then understood. He had been the cause of much trouble for the men in the past, why should they now help him out? What could he do to win them over?

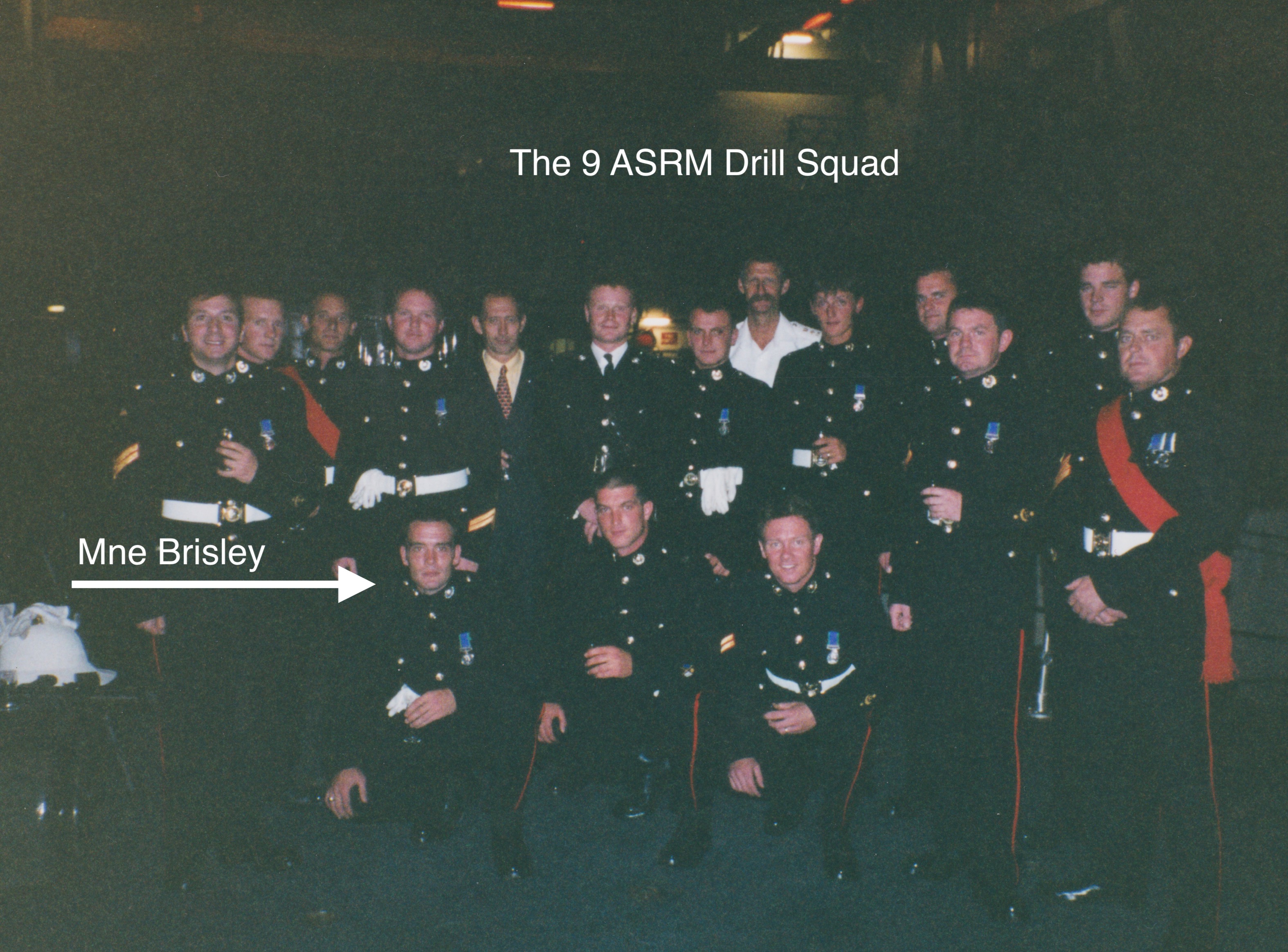

Well I would like to say that he performed some textbook leadership example to do this, but he did not. He bribed them with beer and he got his twelve men out practicing the drill routine that he had developed. Over time, his hard work paid off, they actually enjoyed his leadership and the imaginative programme he had dreamt up. The routine was enhanced as the drill improved. By the time we got to Malta, the rehearsals drew regular crowds of ships company, eager to see what ‘Royal’ was doing. The drill display was now a silent routine (no commands given) of timed choreographed steps, weapon handling and memorably excellent precision moves.

The response

The Ship’s Captain and guests were both impressed and delighted. He moved to congratulate me since he imagined that I had devised the whole thing. I was able to step aside and introduce him to the man behind it all. A rather surprised Captain noted that Marine Brisley had pulled it off in style. The Squadron rallied around Brisley, a clear example of someone who had achieved a substantial change in direction.

So, why my gut feeling?

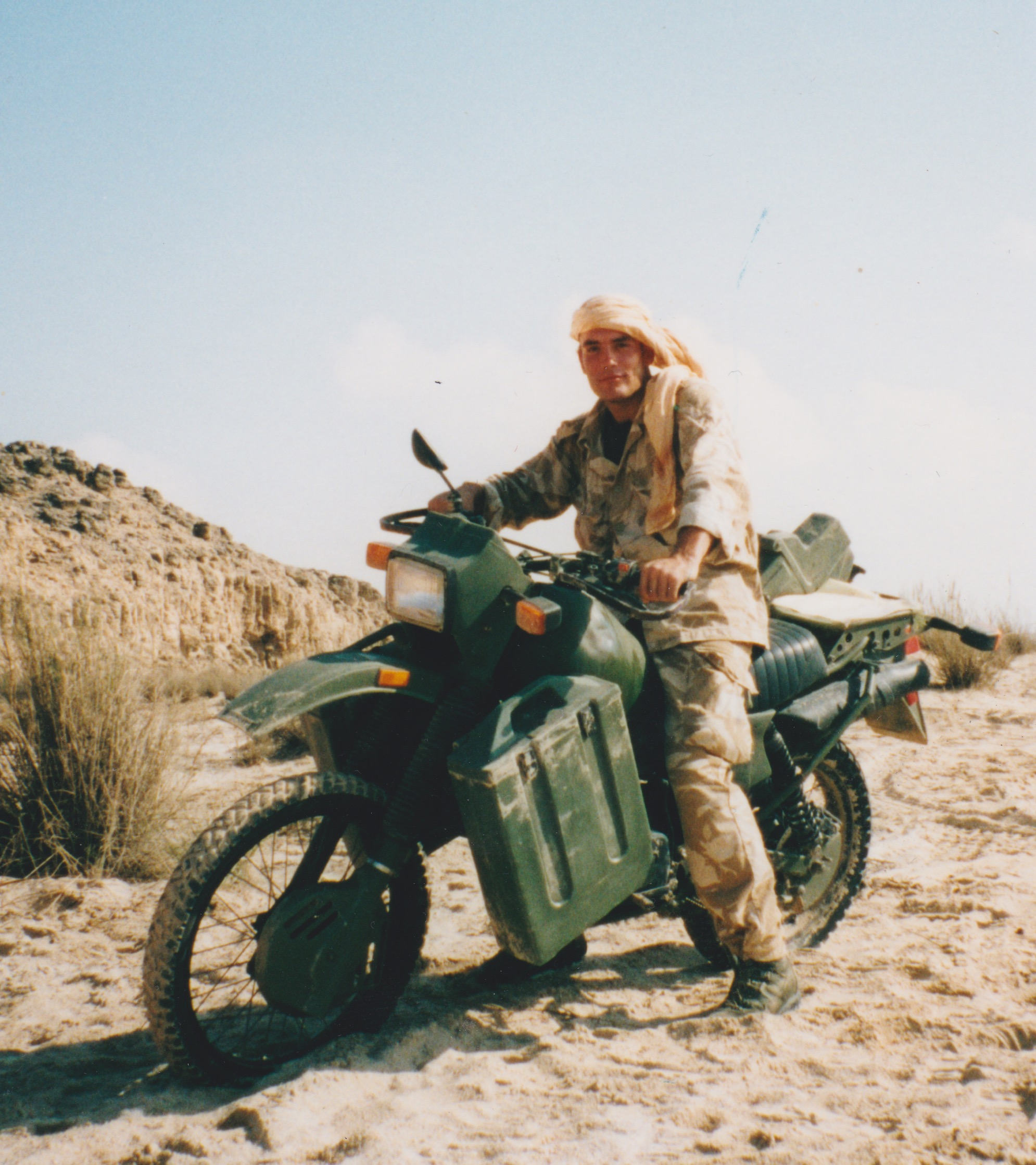

The Marine Brisley that presented himself at the Orderly Room had been in the Squadron for some time. I knew him to be better than he had currently been behaving. The year before we had deployed twice on operations to Sierra Leone at no notice. Marine Brisley had been a central character in the good performance of the entire Squadron. He had demonstrated some good leadership attributes and offered ideas for improving our effectiveness. One day, during Operation SILKMAN, I received a welfare signal informing me that Marine Brisley’s mother was critically ill in hospital. We were to make every effort to get him home. He was out in a Landing Craft at the time. His fellow marines packed some gear for him and assembled money, travel documents, food and water for him. I recalled his landing craft to the ship and a helicopter was made ready. When he arrived back at the ship I had only enough time to explain the situation and tell him that everything he needed was in the helicopter. He ran off, fully aware that his oppo’s (a Royal Marines term for a friend) had supported him when he most needed it.

The helicopter flew him to Lungi airport where he boarded a plane to Dakar and then on to London. A Royal Marines Sergeant met him and sped him to the hospital in London where he arrived just in time to hold his mothers hand and express his love for her before she passed. We all felt good about that.

Such had been his place in the Squadron that that the troops rallied to support him. It was really after the return to routine duties on ship in Plymouth that Brisley started to stray. This is not at all unusual for young men who have tasted the adrenalin and buzz of operations. I think that was what lay at the back of my mind when I was figuring out how to deal with his trouble making.

Return to UK

Post the Malta visit and various amphibious exercises we returned to UK and an opportunity arose for the ship to embark family and friends for a short overnight trip for Marchwood to Plymouth. I encouraged Marine Brisley to bring his close family, which he did. Their sense of gratitude for what the Royal Navy and Royal Marines had done to get Brisley back to see his Mum and for the clear changes in his character for the better was almost overwhelming.

Brisley went on to join the newly formed four-man rock band called The Crows. They played for the families. His interests were widening and I had no difficulty recommending him for promotion.

I posted off the ship and he left soon afterwards to start his NCO training. He passed and joined 42 Commando Royal Marines as a Section Commander leading seven marines in a Rifle Company.

Next meeting

I saw him briefly for a drink and a catch up when I returned from the invasion of Iraq in 2003. He was keen to know what it had been like and how the ship and Squadron had performed. He was in good spirits and enjoying leading his Section.

I met with him again just before he deployed to Afghanistan. The Corps was fully involved conducting regular deployments to Helmand. Marines were experiencing some of the toughest fighting since the Falklands War. He was excited but mindful. He knew this would be a defining moment. I reminded him of where he had come from on his journey to date and we parted with a firm handshake and the knowledge of a journey shared.

Helpful leadership

On his return and knowing that the Unit had had a particularly brutal six months in action I called him to agree a meet up. We sat in a pub in the Barbican in Plymouth and as men do, when they are comfortable with their company, he poured out the emotions of his experience. It was as he had expected, a defining moment in his life as a leader. The Tour was full of danger, trauma and action. He lost close friends, saw terrible things and had never been so frightened. He had come through it though and led his men well and they had accomplished good things despite the hell they had experienced. I asked him how he was coping. He said all was well.

In fact, he got up in the morning, made his wife breakfast then drove her to work in Plymouth City Centre. He would then park up and wait for her to finish and collect her at the end of the day. What did he do between nine and four, I asked? Without any hesitation, he responded by saying that he would go and sit on a bench and watch the world go by (for seven hours!). I asked him if he thought that was a good use of his time. He said it gave him time to think but he had been doing this now for five weeks and maybe, I urged, it was time he went and sought some professional help. He did.

Over the following years I saw him when he was a qualified Drill Instructor training recruits at the Command Training Centre Royal Marines; he loved it. He was now truly enjoying life, his goal fulfilled.

Tragedy and leadership

My oldest son Jamie, a Royal Marine, was killed in an accident at Lulworth Range in 2008. I was on Rest and Recuperation from a Tour in Afghanistan at the time and now found myself trying to cope with the grief of losing him and organising his funeral. Sergeant Brisley heard and reached out. Jamie was cremated with full military honours. Sergeant Brisley worked tirelessly with another former Royal Marine “Baz” Thrift (a retired Warrant Officer who I had taken through training in the late 1980s) to organise the ceremonial side. It was flawless and wonderful and as good as such events can be in the aftermath of tragedy. I will always be grateful to them both for that.

Later, I became the Director of Training at the Commando Training Centre Royal Marines. Who should be the senior Drill Instructor? None other than Colour Sergeant Brisley! We had coffee catch-ups and a few laughs about the way things had panned out. What a pleasure seeing this now highly professional man, doing what he was good at.

Brisley retired from the Royal Marines in January 2018 as a Warrant Officer. He afforded me a lovely accolade by inviting me to his Top Table. The Top Table is a fine tradition in the Sergeant’s Mess of the Royal Marines. On retirement, a lunch is held to formally recognise his service. He can invite all those (past and present) who meant something to him during his career. The lunch is punctuated with reminders of the highs and lows of his career with many dits (stories) being told. That is why I wrote this article. I can’t be there but it is important that his story is told.

So what?

Nobody, least of all me, can predict the future or see the impact that decisions made will have on a man. One can imagine though! In leadership terms it would have been easy to dismiss Marine Brisley as trouble and get rid of him; indeed I thought about it! Something told me that he was a keeper. Yes, I was taking a risk on him. Yes, it was potentially going to mean more trouble than it was worth. However, on reflection, I am very happy that I chose the path that supported this young Marine when he needed it. He turned out well. Brisley leaves the Royal Marines on an absolute high. He has in turn, led and influenced so many more men for the better.

I shared this article with him before publishing and he said, “you are the single biggest factor in the outcome of my career……. the orderly room pre Malta was my crossroad and you gave me the ‘chance’; things would have ended differently indeed if you hadn’t helped me then. It is and has always been on my mind when I have had to deal with defaulters of my own and every time I’ve checked myself as to how I got to where I did”.

In life, as leaders, there are times when you just need to go that little bit further. You have to go with your instinct and give someone a chance. As this tale demonstrates, you and others will ultimately benefit from the “greatness” that is in us all.

Written by Jim Hutton, OBE for Anthony Brisley